People before protons: How to pitch a science story

by Monte Stewart

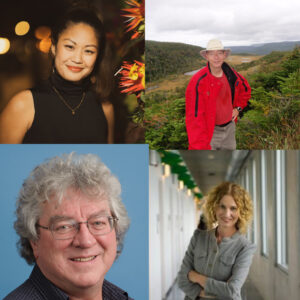

Yasmin Tayag, Tim Lougheed, Leah Geller and Mark Lowey

Tim Lougheed has been guarding his secret for years.

If he has his way, editors will never pry it out of him.

“To other people, I will call myself a science writer,” he said. “If I’m selling a story, I will never use that term.”

And Lougheed is adamant that he will not disclose his preferred subject area, either.

“The way to sell a science story is to never – ever, ever – use the word science,” said Lougheed, who is based in the Kingston, Ont., area. “I always lead [the pitch] with the story first.”

“I think: This is just a story. When you’re doing the pitch and you’re coming up with that lede, you put [the idea] together as if it would fit into any category whatsoever and say: This is a really cool story about why this angle does that.”

Such moves have paid off. Lougheed has been freelancing full-time about animal research, microscopes, isotopes, phosphorous, fuels and several other science-related matters for about three decades.

“I started with science, and it’s been very good to me – let’s put it that way,” said Lougheed, who was a staff writer with the Windsor Star, Sault Star and Queen’s University communications department before becoming self-employed in 1991.

New COVID-related freelancing opportunities

Lougheed fessed up to his strategies and, along with other science writers and editors, offered tips for freelancers seeking potential science writing opportunities in wake of COVID-19. The prevailing theme among those interviewed? A so-called science story is not just about science.

He said COVID-19 has created many new freelancing opportunities, particularly for “explainers.” But to capitalize on the opportunities, freelancers must first overcome a fundamental fear of scientific subjects.

“Science is actually a wonderful lens through which to view a lot of story possibilities, because not a lot of people cover it,” he said. “That’s not to say there’s nobody doing it but, relative to other areas, a lot of freelancers shy away from it.”

When considering a sellable story angle, Lougheed does “triage” to see whether it breathes, can be saved, or is doomed. He advises writers fearful of science writing to look beyond a press release, get “under the hood” of a topic’s history and, most importantly, bring out the people connected to the relevant science, along with their love for it.

“They are seen to be remote and inaccessible by a great many people that write but, in fact, scientists are well worth the trouble [of interviewing],” he said. “The things they are doing, the things they are exploring, the motivations they have for their work are endlessly fascinating – and make wonderful grist for our mills.”

More opportunities for journalists of colour

Yasmin Tayag, a senior editor at New York-based online science-and-technology publication OneZero, said she prefers to commission pieces about people, particularly the ones a science story affects and those doing the research, because they are easier for lay readers to connect to.

“The most important thing, to me, is making clear why a reader – especially one who isn’t particularly inclined toward science – should care about the science story that’s being pitched,” said Tayag, who grew up in Toronto and also writes a coronavirus blog.

In her view, a good science story is also easy to understand and does not talk down to the reader. The story becomes newsworthy when the science “has a real and palpable impact on people.”

“This can be an immediate impact,” she said. “For example, coverage about what we do and don’t know about the transmission of COVID-19 is shaping the way the public behaves in real time. But it can also be a longer-term impact, like coverage about the disproportionate effect of environmental pollution on Black communities changing how readers think about pollution in general.”

Tayag is heartened by an increase in published stories about social, cultural, and racial biases in science and science coverage. She points to many stories about how low-income and people-of-colour (POC) communities are the most affected by climate change, and the fact that a lot of COVID-19 coverage notes the disease’s disproportionate impact on Black people.

“Further, there are more and more science journalists of colour whose work is getting published,” she said. “I think this is really wonderful and encouraging, because they have different perspectives that need to be heard.”

Predicting that science coverage will have an increasingly “political flavour,” she said clarity on sources is needed to offset mixed messages, like the ones on mask-wearing and social distancing spread by U.S. president Donald Trump and his administration.

“I think science journalists and scientists themselves are going to play an increasingly large role in informing [the public on] the way people live – since traditional sources of public health information, like the U.S. government, are no longer as reliable,” said Tayag.

Scientific expertise helpful, not essential

Leah Geller, an Ottawa-based writer and editor and member of the Canadian Freelance Guild, said she has also observed the politicization of science in Canada, but she views “the corporatization of science information” as a bigger threat.

She hopes intense interest in COVID-19 will lead to more public conversations about credible and non-credible science-information sources.

Great science stories, she added, are timely and relevant to the reader, challenge assumptions and leave the audience with “a sense of awe and wonder.”

Scientific investigation tends to be long-term, but Geller said COVID-19 is making research stories timely because the disease is “front of mind” with readers.

Although science writing opportunities with traditional media outlets have declined significantly, she added, opportunities to write for universities, hospitals, research centres, companies (such as biotech firms) and other organizations are increasing.

“There’s less of science journalism, science reporting, and more of science communicating on behalf of these organizations,” she said.

Geller was a pre-med student at McGill, where she obtained a Bachelor of Science degree in human physiology and also worked as a clinical and laboratory researcher and wrote for the university’s newspaper, before opting for a writing career.

Scientific expertise is helpful, she added, but passion and enthusiasm for the subject matter are more important.

“I think it’s really good to have scientists in the journalism field – I don’t think it’s essential,” said Geller.

Local angles open doors

Mark Lowey is an award-winning Calgary-based freelancer who has excelled in science-related writing despite lacking extensive science education. Lowey holds an English degree from the University of Calgary and says that he did not do particularly well in the few science courses he took.

“[Because of] the way it’s worked for me, and not just for COVID-19 [stories], I think you have to know your local audience and your local market and find some sort of local niche angle,” said Lowey. “The science writers that are already well-established are already going to be writing big pieces on COVID-19 for Scientific American and other publications [catering to a global audience]. But if you can find something local, that you can even pitch to your local newspaper, then I think you’ve got a better chance of actually breaking in in that market with a story.”

Like Lougheed, he does not describe himself as a science writer, and says that he has not written a “pure” science story for a long time. A regular contributor to Research Money magazine, Lowey has mixed science into many stories about energy, the environment, medicine and other matters.

“[Pure science stories] are those stories that are focused solely on science,” said Lowey. “They’re the kinds that you read in Scientific American or National Geographic. Science is forefront in the story. And, I don’t think there are many of those kinds of stories being written, frankly.”

Lowey attributed that situation to a dearth of full-time science writers at Canadian mainstream publications, and reduced demand for long narratives and even short news hits due to media companies’ financial struggles. But, he noted, many freelance stories with science components are still being published.

The key, he said, is to hook the science to a broader area – “even business” – and make the story appeal to readers while also providing clarity and plenty of context.

“You really can have any topic that has something to do with science,” said Lowey. “And if you write about it in an engaging way, then you’ve got yourself a science story.”

Monte Stewart is a freelance journalist based in Vancouver. He covers sports, business and other topics for wire services, newspapers, magazines and online media outlets in Canada, the U.S. and Europe. You can find him on Twitter at @MonteStewart.