Freelancer Katie Jensen talks about the importance of income transparency in Canadian media

*Editor’s Note: July 28, 2017. This post has been updated to include an addendum to clarify certain points raised in the Q+A.

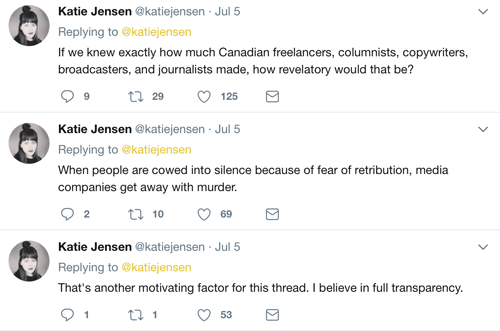

On July 5, freelance podcast producer Katie Jensen publicly shared her 2016 net income as part of a Twitter thread she hashtagged #incometransparency.

The 29-year-old has been in the freelance business for little over two years. She says she decided to be transparent about how much money she makes and what her work experience has been like in order to start a much-needed conversation about the reality of being a journalist in Canada.

She took the time recently to speak to Story Board about working conditions for young journalists and to share some tips for freelancers.

Why did you decide to start a public thread about income transparency?

I wanted to talk about income transparency because I feel like a lot of people overestimate the amount of income that journalists make. If you [do a search online], the numbers that show up are like $60,000, but that number is so foreign to me. Even H.G. Watson, who is the editor for J-Source, said Stats Canada reports that the average income for journalists is $46,000.

The morning I did the thread, I got an email from the CRA telling me I owed $4,000 in back taxes from last year, so I guess I was feeling a little bit candid.

Why do you think income isn’t a topic that most people talk about?

I think people are embarrassed to ask about what other people make. I think it’s a [fear] of being socially impolite rather than a sense of “I don’t make enough money.”

You talked in your thread about working a lot of unpaid overtime. Can you tell me a bit about that?

I started out as an unpaid intern at Canadaland and I worked as an unpaid intern there for a few months. If I were to do it again I would have negotiated for minimum wage, because I think working for free establishes a sense of a young person willing to do anything to get into the industry. If I could go back, I’d turn to my younger self and say, “know you’re worth something.”

After interning, I worked there for two years. [Working unpaid overtime] is almost like when you visit home after being at school in the middle of school exams. You have no patience for anyone’s jokes and you can’t listen to anyone’s stories because you’re so just focused on these exams that are hovering over your head.

Working in such a high-pressure environment felt like I was in crunch exam time constantly.

Were there any benefits to working with Canadaland, or was it just pure grind?

I would say the benefits were that it made me realize that the world of Canadian journalism is only as closed off as you think it is. If you just make the effort and network your ass off, you can get somewhere. People will give you the time of day, you just need to prove to them why their time is worth spending on you.

But I haven’t felt that same grind since then—I think it was a Canadaland thing.

Do you think these kinds of working conditions are standard in Canadian media?

Well we don’t know, and that’s the whole point. We don’t know what other people make, so we’re assuming one thing when really it could be totally inaccurate.

What are some strategies you have for making life as a freelancer easier?

I think knowing thyself is important. You need to know if you’re the kind of person who likes to organize themselves and their business electronically or on paper. I have my notebook that has every single client conversation I’ve ever had in it.

With freelancing, you never really know when you will get paid or what project you will be working on in any given day. You need some structure within that — for example, saying that your work hours are between 9 a.m. and 7 p.m.

Finding out what kind of organizational tools you like to use and then sticking to them is super important. I am all about productivity tools. For example, I use Trello, which is a team organizational tool. And I use TimeBridge, which is like a public calendar.

What about people who are new to freelancing, what would you say to them?

Open up a lot of tabs and do a lot of research.

Message that one person you know who is a freelancer and just say “hey, I am thinking about doing this, can I run this by you?”

Also, get a website because if you don’t have one you won’t get any inbound work. Your website should act as a business card you leave on the street or a poster in a coffee shop. It’s the kind of thing that not enough journalists do.

You mention in your thread that you wait until an invoice is two to three weeks past due before following up on it. Has that been effective for you?

It has been very effective for me, with the exception of one client. Why should you feel bad about asking for what you’re owed? As a freelancer, you have to sort clients into good eggs and bad eggs and know where you’re spending your time.

I will bend over backwards for a client or editor that I know wants to nurture our relationship. If you put the same amount of energy into every single relationship, you will burn out and you won’t make any money. You have to know who and what is going to get you paid.

As a freelancer, you want to invest the most time in making sure that you are progressing your career and also doing work that you love.

Why do you think it would be “revelatory” to know how much Canadian journalists make?

I think because it would show how many junior people are lifting up the chairs of people in senior positions. It’s this system where you’ve got all these anonymous writers and anonymous producers and you don’t know these people exist because they’re not getting their voices on air.

That’s just the reality of what we have to live with right now. But I do think that if we were honest and open about our income then people wouldn’t think that journalists were such an elite class.

What do you think are some solutions to the issues you brought up in your Twitter thread?

I think everyone within Canada should be making a living wage respective to the city they’re in. A journalist living in Edmonton should be able to afford to live in Edmonton. But they should also have the flexibility that, should they no longer want to live and work in Edmonton, they aren’t stuck where they are.

If you want to make it as a freelancer, you need to figure out how it can work for you. You don’t have to play by anybody’s rules, you just have to make sure that you’re happy and that you’re taken care of. Knowing your worth and then figuring out how to get what you’re worth is tantamount.

At the end of your thread you said you had a lot to think about. What were you left wondering about?

I am wondering how I can turn this into a project or an article where I tell a bunch of stories — like a collage of stories from journalists across Canada.

Vanessa Hrvatin is a Vancouver-based journalist who is passionate about public health and science reporting. Follow her on Twitter at @VanessaHrvatin.

Editor’s Addendum:

- While Katie Jensen worked as an unpaid intern at Canadaland she was a student at Humber College and received course credit for the internship. Canadaland was not under any obligation to pay her in these circumstances.

- In 2016, Katie Jensen worked part of the year as a full-time employee of Canadaland, then with Canadaland as a contract producer. She also earned income from working with students, which combined to a total of $27,000 of net income.

- Canadaland publisher Jesse Brown contacted us in regard to overtime at the workplace. He writes:

“Vanessa and Katie discuss Katie working “unpaid overtime” at CANADALAND. I negotiate with employees to arrive at a list of duties and responsibilities they feel they can accomplish in a 40-hour work week. If in practice, the time spent on the agreed workload exceeds 40-hours, employees are encouraged to tell me. Katie did so when working as the producer for the Imposter, and in response I authorized her to hire a part-time assistant.”