The rise of indemnification clauses in freelance contracts

When Toronto journalist Jesse Brown wanted to break the Jian Ghomeshi story, he knew couldn’t do so on his independent podcast Canadaland. At the time, he didn’t have any libel insurance, and several lawyers told him that while he could take steps to ensure he could win a libel lawsuit, provided he had the funds, there was nothing he could do to stop Ghomeshi from filing suit in the first place. So they advised he partner with a well-insured publication.

“I presented it to a few different partners, and the one I ultimately signed a contract with was the Toronto Star,” Brown says. “And my chief reason for doing so, and the thing I demanded be explicit in our contract, was that they would cover me from any legal consequences. … They understood that completely.”

The Star declined to comment on this story, citing the confidentiality of their freelancer contracts. Whether or not the Star always includes freelancers in their liability coverage, an analysis of freelance contracts offered to Canadian Media Guild members shows that publications are increasingly asking writers to take legal responsibility if their story leads to a libel lawsuit.

“I just think it’s unconscionable to deem a story fit for print, deem it worthy of being published under your masthead and meanwhile, declining to stand behind that story and declining to protect the freelancer,” Brown says.

Enormous financial risk

Alison Motluk, a freelance journalist based in Toronto, refuses to sign contracts with these indemnification clauses. First off, they impose an enormous financial risk on freelancers: defending a defamation suit can cost millions, as seen when Memorial University professor Ranjit Chandra lost a libel suit against the CBC and was ordered to pay $1.6 million in their legal fees.

Furthermore, depending on wording, indemnification clauses may require freelancers to pay for a legal response but allow the publication to decide what that response is. “For instance, you might end up paying for the company lawyer to settle and apologize on your behalf when you don’t mean to apologize,” Motluk says. “Maybe you did nothing wrong. Maybe it ruins your reputation to be seen to be apologizing. [But contractually] you have to pay your share or all the cost of a lawyer actually doing something that’s against your interest. That doesn’t make any sense.”

The trend towards freelancers being required to indemnify publications is connected to “a degradation of ethics and responsibility within the industry that’s going hand in hand with an exploitation of freelance labour and the financial pressures that the industry is under,” Brown says.

“It’s their reputation on the line”

Those financial pressures have led many publications to slash their fact-checking budgets, which may have encouraged them to offload liability onto freelancers, suggests Giuseppina D’Agostino, an associate professor at Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto. “It seems like that’s what they’re doing in order to protect themselves because they don’t have the resources to do it,” she says. “ … What they don’t realize is they’re shooting themselves in the foot, frankly, because it’s their reputation on the line.”

Once Canadaland grew sufficiently, it bought errors and omissions insurance through the Canadian Newspapers Reciprocal Insurance Exchange (CNRIE), Brown says. That coverage includes all writers who have contracts with the insured publication, according to CNRIE spokesperson Lucia Shepherd.

“I knew we couldn’t do our jobs as effectively or bravely as we need to without libel insurance,” Brown says, noting that journalists can be sued for libel without having committed the offence.

What’s published is ultimately the responsibility of the publisher, says Jessica Johnson, executive editor of The Walrus, in Toronto. But contributors to the magazine don’t always see that ethos reflected in their contract.

“I know it’s misunderstood by a lot of people because I’m asked about it all the time,” Johnson says, noting The Walrus recently clarified the wording in its freelance contract but kept the same terms. “I was spending time on the phone with people … saying, ‘Look, this is what your contract actually means.’ Once we had that conversation, people were usually satisfied by it.”

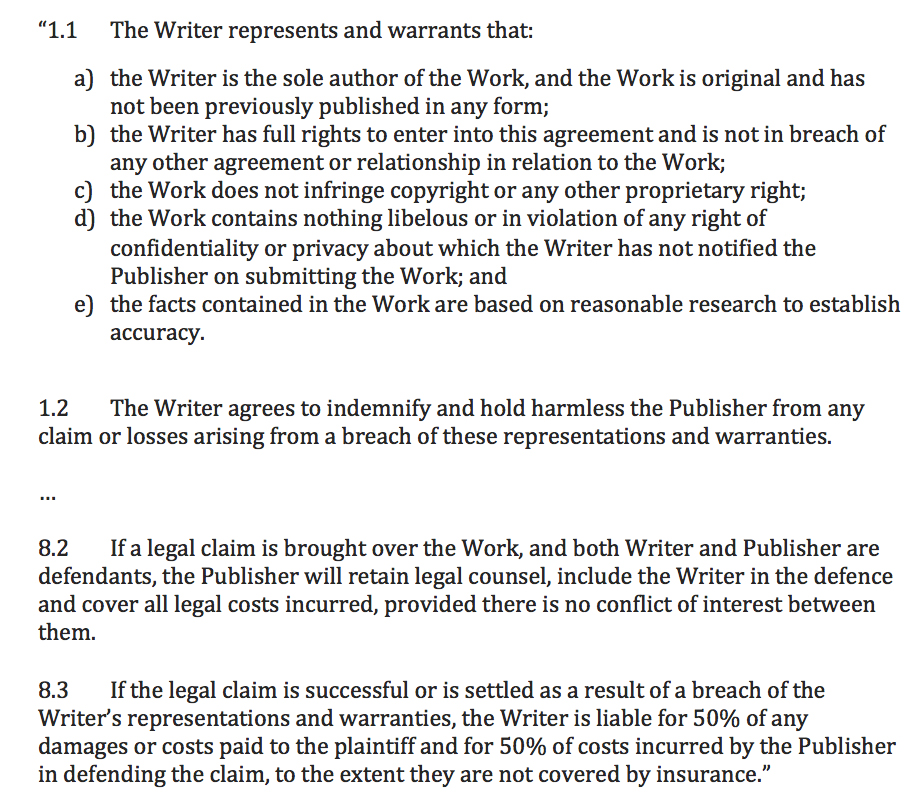

The seven-page contract in question includes the following terms:

The contract doesn’t require writers to indemnify The Walrus from any lawsuits but “to indemnify the publisher from any breach of the writer’s responsibilities and warranties,” Johnson says. That includes making up sources, deliberately lying to editors, and failing to tell a subject the story is being written or giving them sufficient time to respond to accusations.

I suggested that section 1.2, when read in light of section 1.1(d), requires writers to indemnify the magazine for losses tied to a libel lawsuit. Johnson disagreed, stressing the second half of the 1.1(d) clause: “the Work contains nothing libelous or in violation of any right of confidentiality or privacy about which the Writer has not notified the Publisher on submitting the Work.”

“If I am a writer and I’m writing a difficult story, which is often the case, and I tell the editor, ‘So-and-so is going to be weird about this,’ or ‘I don’t feel right about this,’ or ‘I’m worried about this,’ then you’re fine,” Johnson says. “You have done your due diligence and you have let us know there’s possible legal sensitivity around something. … If you have done your job, you don’t need to worry.”

Make sure you have written evidence

If discussions about legally sensitive issues do take place, however, CMG Freelance president Don Genova advises freelancers to make sure they have written evidence of those discussions if they take place in person or over the phone.

“It would be advisable to sum up any conversations with a follow-up email to make sure everyone is on the same page. Or to save email threads in which these types of discussions take place,” he says.

In its 15-year history, The Walrus has never been successfully sued, Johnson says, emphasizing the defense of truth to defamation claims. That is, subjects don’t have a case if the article is true. So the magazine has an extensive fact-checking process, and has killed stories if they don’t pass muster. As for section 8.3, The Walrus requires freelancers to pay 50% of legal fees is they are found guilty of libel but not if they are acquitted because, in the latter case, they’ve done nothing wrong.

“I don’t know how a contract could be more friendly than ours is right now,” Johnson says.

Click here to read part two of this series: What should you do if a publication asks you to sign a contract with an indemnification clause?